Introduction

Pteridophytes are a group of seedless, spore-producing vascular plants that have successfully adapted to life on land (first true land plants), typically growing on moist and humid habitats.

The term Pteridophyta is derivation of Greek word, where “pteron” means “feather” and “phyton” means “plant.” Plants in this group have feather-like fronds or leaves. Pteridophyta is classified under Cryptogams along with Thallophyta (algae and fungi) and Bryophytes.

Among these, Algae, Fungi, and Bryophytes are referred to as lower cryptogams (non-vascular), while pteridophytes are known as higher cryptogams (vascular) due to their well-developed conducting system, making them the first true land plants.

Pteridophytes have a long fossil history, dating back approximately 380 million years. Fossils of these plants have been discovered in rock layers from the Silurian and Devonian periods of the Paleozoic era, which is sometimes referred to as “The Age of Pteridophyta.” Fossilized pteridophytes ranged from herbaceous plants to tree-like forms.

Resemblance of Pteridophytes with Bryophytes and Gymnosperms

In the plant kingdom, pteridophytes hold an intermediate position between bryophytes and gymnosperms, sharing characteristics with both groups.

They resemble Bryophytes in following ways:

- The presence of a sterile jacket around the antheridium and archegonium.

- Need for water and moisture for fertilization.

- Occurrence of alternation of generations.

- The formation of spores.

On the other hand, they share similarities with gymnosperms are;

- Presence of independent sporophytic plant body.

- Differentiation of the sporophyte into roots, shoots, and leaves.

- The presence of vascular tissues for conduction.

The presence of vascular elements in pteridophytes groups them with gymnosperms and angiosperms under the category Tracheophyta.

However, their reproduction via spores and similar life cycle events align them with lower plants. Historically, lower plants like algae, fungi, bryophytes, and pteridophytes were grouped together as cryptogams.

Bryophytes, pteridophytes, and gymnosperms are also classified as Archegoniatae due to the common presence of the reproductive structure known as the archegonium.

General Characteristics of Pteridophytes

- The main, independent plant body in pteridophytes is the sporophytic and consist of a vascular system.

- They usually grow in cool, moist, and shady environments, but some are aquatic (e.g., Marsilea, Salvinia, Azolla) and a few are xerophytic (e.g., Selaginella rupestris, S. respanda, Marsilea rajasthanensis, Marsilea condenseta).

- These plants are differentiated into true roots, shoots, and leaves. However, some primitive members lack true roots and fully developed leaves, such as those in the orders Psilophytales and Psilotales.

- Except for a few woody tree ferns, all living pteridophytes are herbaceous.

- They may exhibit dorsiventral or radial symmetry and have branched stems.

- Leaves vary, from scale-like leaves (e.g., Equisetum) and small, sessile leaves (e.g., Lycopodium, Selaginella) to large, petiolate compound leaves found in true ferns.

- The stems bear leaves that can be either microphyllous, with small leaves and an unbranched midrib (e.g., Lycopodium, Selaginella, Equisetum), or megaphyllous, with large leaves and a branched midrib (e.g., ferns).

- In ferns, young leaves exhibit circinate vernation, meaning they are curled inward.

- Primary embryonic roots are short-lived and are replaced by adventitious roots.

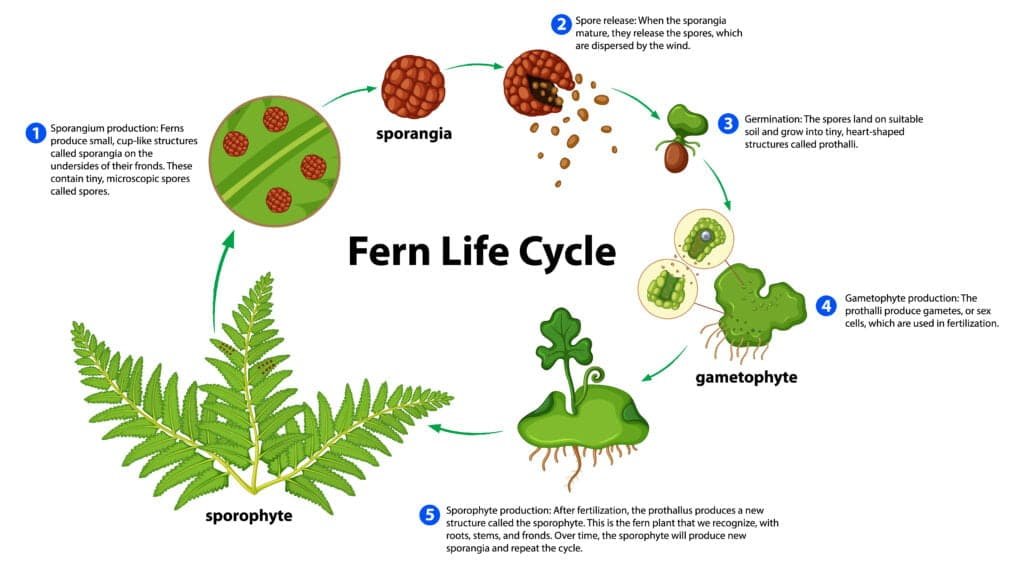

- They reproduce through haploid spores produced within specialized structures called sporangia.

- These plants can be homosporous (producing spores of the same shape and size) or heterosporous (producing spores of two different shapes and sizes: microspores and megaspores).

- In some pteridophytes, sporangia develop on the stems in the axils between leaf and stem or on the leaves, usually on the ventral surface. On the stem, sporangia can be terminal (e.g., in Rhynia), lateral (e.g., in Lycopodium), or located on the surface of leaves (e.g., in ferns).

- Sporangia borne on the ventral side of a specialized leaf are called sporophylls. In aquatic ferns, microsporangia and megasporangia are enclosed together by a common membrane, forming a bean-shaped structure called a sporocarp.

- In true ferns, sporangia are located on the lower surface of the leaf in clusters known as sori (sorus).

- The haploid spore serves as the unit of the gametophyte and develops into a gametophytic prothallus upon germination.

- The gametophytic plant is called a prothallus, as it resembles the thallus of a primitive bryophyte.

- The gametophyte bears sex organs called archegonia and antheridia. A zygote or oospore is formed as the result of fertilization.

- Homosporous plants are typically monoecious, with antheridia and archegonia on the same thallus.

- Heterosporous plants are usually dioecious, with antheridia and archegonia on separate thalli.

- The microspore develops into a male prothallus that bears male sex organs (antheridia).

- The megaspore develops into a female prothallus that bears female sex organs (archegonia).

- The sex organs are either embedded in or projected from the prothallus.

- Male gametes, known as antherozoids, are produced inside the antheridium.

- Antherozoids are unicellular, spirally coiled, and flagellated.

- Archegonia are flask-shaped and differentiated into an upper neck and a lower, broader venter.

- The neck of the archegonium is projected, while the venter is embedded in the prothallus.

- Water (moisture) is essential for the completion of fertilization.

- The egg and antherozoid fuse to form a diploid zygote, which then develops into a new sporophytic plant body.

- They exhibit a clear alternation of generations in their life cycle, which is always of the heteromorphic type.

Habitat of Pteridophytes

Pteridophytes are the first vascular plants to inhabit land, so they are primarily terrestrial, thriving in cool, moist, and shady environments. However, some of them also grow in xerophytic, semi-aquatic, or aquatic conditions.

Terrestrial Pteridophytes

- Members of Pteridophyta, including ferns, typically grow in terrestrial habitats.

- Some pteridophytes are lithophytic, growing on horizontal rocky surfaces.

- Fossilized pteridophytes were also terrestrial. Common species of lycopods that grow in such habitats include Lycopodium clavatum, L. cernuum, L. reflexum, Selaginella chrysocoulus, S. kraussiana, and I. coramandelina.

- Additionally, some pteridophytes are epiphytic, such as Psilotum nudum, L. phlegmaria, S. oragana, and certain ferns. These epiphytes thrive on tall, well-stratified trees in forests, sharing their niche with orchids and other ferns.

- Some prefer open tree trunks and branches.

Aquatic Pteridophytes

- Certain pteridophytes grow in aquatic and semi-aquatic habitats.

- Examples include Isoetes panchananii and I. englemanni, which are semi-aquatic.

- Some ferns, commonly referred to as water ferns, include species like Marsilea, Salvinia, Azolla, and Regnellidium.

Xerophytic Pteridophytes

- A few species of Selaginella and Marsilea are adapted to xerophytic conditions.

- Examples of these xerophytic pteridophytes include S. repanda, S. lepidophylla, M. rajasthanensis, and M. condensata.